Ghadai, an exhibition by the potters of Kachchh

In some areas of Kachchh, you might see the homes of potters piled with waste plastic, old tins and cans; the image of the classic scrap dealer we are familiar with. This is the profession now for many potters in Kachchh. They are known as Kumbhars, derived from the word kumbh - broadly translated as a pot.

How did a Kumbhar become a scrap dealer?

Ghadai, by the Kumbhars of Kachchh, tells this story – tracing it from the present day to its immediate past to the ancient sites of the Harappan civilization that once flourished in this region.

The Kumbhars

A potter was in great demand just 40 years ago. No new settlement could function without their presence. Potters were specially invited to set up their homes and work shops if there was more work or the village was relocating. All the present day potters in the still active pottery clusters of Kachchh have arrived there from somewhere else. The Maharao of Kachchh, Rao Khengarji in the 15th century, himself, invited a colony of Potters to his capital Bhuj, gave them land to live and work and service the communities in his kingdom. There are over a hundred clans or nukhs among the Kumbhars that follow either Islam or Hinduism. Today, there are very few Hindu potters in Kachchh who practice this craft.

While there are potters all over India, the Kumbhars of Kachchh come from a lineage that makes their products and practice distinct. The Kachchh Kumbhars believe their forefathers migrated from the Sindh region. There is enough archaeological evidence to show that there is a commonality of pottery motifs, styles and techniques between the Sindh and Kachchh regions.

Kumbhar Women

Kumbhar women are co creators of the pottery in Kachchh. They are very skilled in the painting on terracotta before it is fired and lend it a distinct identity. While women also mix the clay and help with the firing process they do not generally work on the wheel. They make the choolahs (traditional cooking stoves) and the earthen portable stoves used for heating and cooking. And some women are adept in the making of large storage pots by hand. Clearly, they are indispensable to the pottery practice of Kachchh and none of the pottery clusters would be able to function without their unique relationship with the clay.

The Clever Kumbhar

There were organized economic structures in the pottery community that continued to exist until almost 40 years ago. This system was popularly known as garaas, and ensured lifelong patrons for every artisan. Usually the garaas were the asset owning communities of farmers and pastoralists. The patronage was passed on in the families and the generations of both sides were expected to honor these ties. The patrons would be serviced for every need of their family whether they were water pots, or storage pots, cooking vessels or ritual objects by their appointed potters. In return they provided a fixed amount of grain for the potter’s family. A potter’s family could have up to 20-25 garaas families that they would service. There was also a social relationship that bound the garaas families along with the economic one. This relationship was strong and sacrosanct. But as the following folklore shows, you could also swap your garaas!

The Kumbhar went to the jeweler with the 20 diamonds. As the jeweler counted the diamonds, he slyly slipped one into his lap and returned them saying there were only 19. The Kumbhar pretended to count them again and also slipped one into his lap. He gave the diamonds back to the jeweler saying indeed there were only 19 and could the jeweler make him a necklace with these 19? The jeweler agreed but when he set to work he found only 18! As he was now bound by his word, he had to complete the necklace with the promised 19 by adding the one he had stolen. The Kumbhar shone in the end.

The Characteristics of Kachchhi Pottery

The Kachchh style can be described as earthenware, commonly known as terracotta. While other forms of ceramics are now common, including stoneware (used by studio potters, which vitrifies at 1200 degrees celsius), porcelain (matures between 1300 degrees celsius), and industrial ceramics, most civilizations began by using earthenware.

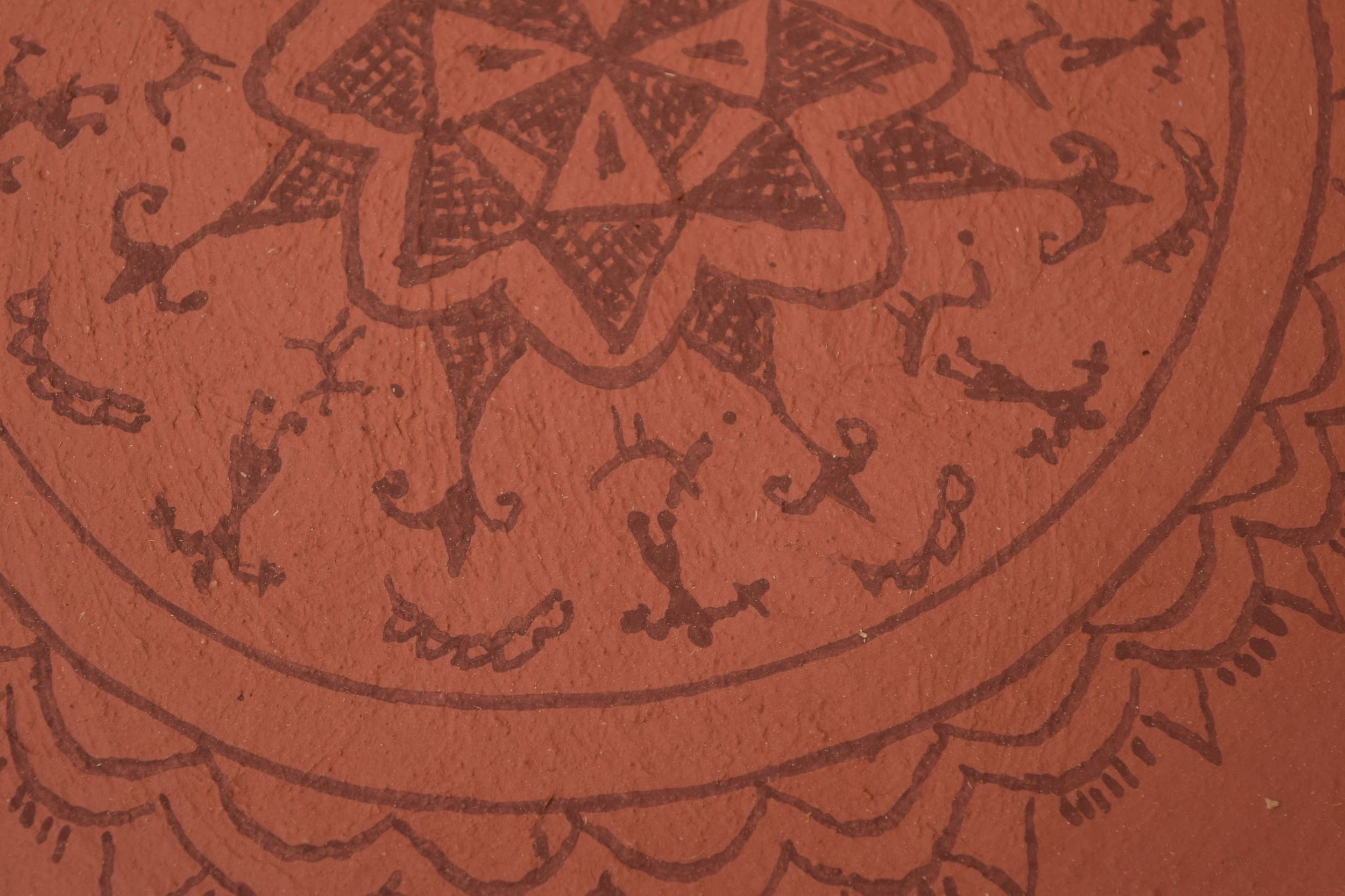

The earthenware clay body matures in the kiln at a temperature range of 800-1050 degrees celsius. Most of the practice of pottery in Kachchh falls under this category. Earthenware in Kachchh is distinct in its use of slips, a watered down clay body with coloring agents added for embellishment. Kachchh Kumbhars use natural red soil (geru) black powdered rock and white clay for this embellishment.

The forms and shapes of the various Kachchhi products show remarkable variation and uniqueness. They differ according to the user communities and are specific to the function they played within that community. Objects were selected for utility, customs and preferences of aesthetics rather than strict social norms of identity.

The range of clay in Kachchh is mainly red and white. The slips used have been in combinations of red, black and white in stylistic forms that ranged from folk, geometric and floral. The painting style was mainly free flowing with bold strokes. The objects were painted before the firing so they became an integral part of the object with a long durability. Till Kachchh was still a part of the Sindh Province (now in Pakistan), there was some exchange of glazed ceramic ware which was a skill in the Northwestern Frontier connected all the way to Turkey and the Middle East.

The Elements

Pottery uses the basic elements of earth, fire, and space in its making. Earth is its raw material, water gives it plasticity, fire strengthens it, and the 3-dimensional object defines space within and without.

The Potter and the Pot - who created whom? Embodied in both are the elements that create the potency for the human body and the earthen pot to be utilitarian, spiritual and aesthetic all at once. And as the human form and spirit journeys from birth to death, we embrace pottery at each milestone in our transitions through life. The use of earthen pots and elements in our rituals at birth, marriage and death also mark an emotional acceptance of the same five elements within us, as that which makes the pot; a celebration and surrender to the clay that made us, and to which we return.

The Process

1 - Identification and preparation of clay

2 - Throwing

3 - Tapping

4 - Painting

5 - Firing

6 - The Unknown sense

Challenges of the potters today

Khamir-SETU conducted a study in 2014 on the work status of potters in Kachchh. A total of 145 potters’ families were interviewed in 54 villages across Kachchh. Below are some of the key findings.

Clay Sources

Many Potters are facing encroachment of their clay sources by farmers, industries and traders. Clay sources are getting increasingly polluted due to dumping of waste by industries in some of the clusters. Farmers and industries are lifting vast quantities of clay from these areas, depleting the source. Some of the clay sources have also been cordoned off by the army.

Generational Change

Pottery practice is hard work that requires the involvement of the entire family. Yet the low financial returns mean that many younger family members do not want to get involved anymore.

Potters are spread across all the villages of Kachchh, making it more difficult for them to protect their interests by putting up a united front.