Khatris are perfectionists

Artisan source: Khatri Musa TarMohammed, Ajrakhpur

“Once, there was a King who invited artisans to display their work in his palace. One artisan presented a mural with a carving of running horses. But the artisan had one request. The King should not allow Khatris to see his work. Word of the exhibit soon spread and many people started visiting the palace. One day a man entered. he observed the mural and hereafter asked to meet with the artisan. He pointed at the piece and explained that since the horses are running, there should be sand in the wind around the legs. He declared the artisan’s piece as imperfect! The artisan now realized that this was a man in disguise. Indeed it was a Khatri!”

The Khatris are an artisan community in Kachchh. “Rang utharna aur rang chadana,” the art of adding and removing color, has been their work for centuries. Originally from Sindh, the Khatris practice crafts like block print, batik print, tie and dye, and rogan painting. There are both Hindu and Muslim Khatris in Kachchh. Jokingly, they claim that at some point in history all their ancestral lines converged.

Oral history establishes a link between the words “Khatri” and “Kshatriya” (warrior). Scholars believe that Khatris expanded beyond their military occupations for economic and political reasons. They became scrbies and accountants in the military, and then transitioned into the more tactile trade of handicrafts.

Block printing

Dyeing

Origins in Sindh

Nothing has come to symbolize the Indus Valley Civilization better than the so-called Priest King from Mohenjo-Daro. The figure is wrapped in a robe-like cloth from its left shoulder under its right arm, and is covered in a trefoil design.

Archaeologists made an exciting discovery at one of the sites of the Indus-Saraswati Harappan civilization. They unearthed 3000 year old strands of cotton dyed with madder (red) at an ancient dyer’s workshop in Mohenjo-Daro, located in modern day Pakistan. These are the earliest textile samples from South Asia.

One of the most celebrated artworks excavated from Mohenjo-Daro is the clay bust of a bearded man, who scholars believe was a priest-king. A trefoil pattern is carved into his shawl. Block printers will identify the trefoil motif as kakkar, a cloud pattern common to the traditional Ajrakh patterns made in Sindh and Kachchh.

The Indus-Saraswati is one of the world’s oldest civilizations, known for its sophisticated infrastructure and inventive material culture. For the last four and a half thousand years people in this region have been masters of naturally dyed and printed textiles.

Remnants in Egypt

Block printed fabric found at Al Fustat. Source: Asmolean Museum

In 1930, hundreds of Indian cotton fragments from the 11th-14th century AD were discovered in Al Fustat, the harbor of Old Cairo. It is likely that they arrived in Cairo via one of many trading ships arriving at the capital’s port from Asia. They remain the earliest example of block printed cloth. The Al Fustat textiles were printed using small blocks, natural colors, and simple patterns. Similar designs are still being printed in modern-day Dhamadka and Ajrakhpur.

From Sindh to Kachchh

Artisan Sources: Razzaquebhai Khatri, Jabbar Khatri (Dhamadka), Dr. Ismail Khatri, Abdul Rehman Budda (Ajrahpur), Abdul Rehman Rasool Soneji (Rapar)

During the 7th century, the Khatris of Sindh were Hindu. It is said that Sindh was invaded by Arabs and forced the people to convert to Islam. Those who converted stayed in Sindh. Those who refused fled to modern-day Kachchh. This was the beginning of a series of mass migrations by the Khatri community from Sindh to Kachchh.

Fabric being washed in the river, Sindh. Source: Sindh Jo Ajrakh, Noorjehan Bilgrami

Resist printing of Ajrakh in Sindh. Source: Sindh Jo Ajrakh, Noorjehan Bilgrami

“Rao Barmalji I, the King of Kachchh, was a patron of craft. He invited artisans from across Sindh to come and settle in his kingdom. We were given land and accommodations. Even the taxes were cancelled for us. So our forefathers from Sindh travelled to Kachchh and settled in the village of Khavda and then Dhamadka. Among them was Jinda Jeeva, our ancestor who came here in 1650. At that time Dhamadka had the River Saran flowing through it. The sweet water of this river was excellent for washing and dyeing.”

While the Khatris of Ajrakhpur and Dhamadka trace their ancestral line to Jinda Jeeva, memories of the Khatris from North and East Kachchh go back only 4-5 generations.

Changing faiths

Many different stories describe how the Khatris in Kachchh came to accept and embrace Islam. Today, Khatri block printers are commonly associated with Sunni Islam. However, there are many Hindu Khatris still in Kachchh as well.

“We were all Hindus at one time. Then we became Muslims. During migration, not all sub castes migrated in equal numbers. Since the Khatris belonged to so many different sub castes, and we had to marry within them, i became difficult. So one Muslim pir came and said that in Islam, marriages are simple. There is no issue of marrying within communities. That is why many people converted to Islam. Our early ancestor in Dhamadka was Jinda Jeeva, a Hindu name, but his son was Abu Bakkar - a Muslim name. This is the history of our families.”

While some Khatris remained Hindu, and some embraced Islam, they continued to work and live together in harmony since time immemorial. In Mandvi for example, the community purchased land for printing work. Khatris could be found at the river’s edge using shared rangchulis (boiling pots). Dyeing at the rangchuli pots became a way for the community to come together and the place came to be known as Rangchuli.

Ajrakh is what we are known for

Artisan source: Dr. Ismail Khatri (Ajrakhpur)

Dr. Ismail Khatri and Jabbarbhai Khatri display a bedspread with Ajrakh design

“Ajrakh is inspired by Brahma, the universe. The blues and the reds of the evening sky and the stars are all inspiration for our cloth. Ajrakh is an Islamic design art with no figures. Everything is crafted using geometrical forms. No other craft’s identity has survived for so long.”

Traditionally, Ajrakh is worn as a turban, shoulder cloth, and dhoti

The word Ajrakh means different things to different people. For the block printer of Kachchh, it is what they are known for. Scholars believe that Ajrakh is derived from the Arabic word azrak, which means blue. According to local Kachchhis, Ajrakh means “keep it today.” Ajrakh cloth is characterized by intricate geometrical patterns, deep red, blues, and blacks, and a complex dyeing process. Originating from Sindh, it has evolved over time into the true identity of block printed fabrics from Kachchh. Ajrakh is the traditional attire of the Muslim Maldharis, the pastoral communities from the region. An Ajrakh turban was a gift for the Maldhari groom at the time of marriage.

“The Ajrakh clothes were of four types: one Ajrakh was bepoti which was used by the aged person, the second type of Ajrakh was dedhi which was worn by a young person less than 15 years of age, the third is savedi used by a person less than ten years old, and the fourth is paniyu, worn by a boy less than six years."

For the Maldharis, the Ajrakh cloth is ideal in the extreme climate conditions of Kachchh. In summer when temperature reaches around 48 degrees Celsius in the desert area, they were a print with a higher amount of indigo which is cooling. In winter when the temperature falls to 10 degrees Celsius, they wear a print with a higher amount of red, for warmth.

Printing of an Ajrakh bedspread; preparation of Ajrakh is a 12-16 step process

Ajrakh cloth is traditionally printed on both sides. Legends say this was made because the Maldhari men needed to get dressed before the sun rose in order to herd their livestock. With double-sided clothes there was no need to fear that they would dress their lungis or turbans inside out in the dark!

Voices across Kachchh

Khavda

“The dyeing techniques of Khavda compared to other villages was the same. But the weather and the water was different, and so the shades of the color were different. For 50 years we were using vegetable dyes here. To my knowledge, there was an ocean here in Khavda. Khavda was called Mandvi ni Beth, and ships came here from Mandvi. But after a major earthquake, there was only land. The things here changed due to desertification of our area and increase in salinity. It is the grace of God that we still have our name in Khavda. Wherever you ask, people will tell you that the Kachchhi ajrakh is available in Khavda only.”

Artisan sources; Indrish Khatri, Kasam Khatri, Rajak Khatri (Khavda)

Mundra

“During the Kingdom days, Mundra was once called the Paris of Kachchh. It was importing dates, sprices, and other such things. Mundra was a prosperous international market. The Bhatias of Kachchh took rice from Kachchh and brought spices and slaves back from Africa. Mundra is a coastal town. The climate here is not good for Ajrakh printing because it requires dry air. Our cloth is Batik, which has not been highlighted like Ajrakh. Batik has been in Mundra for at least six generations. Before Kachchh, our family practiced it in Sindh. IN Mundra we serve the Harijan, Bania, Khatri, Bansari, Patel, and Rabari communities.”

Artisan sources: Khatri Kasam Haji Musa, Shakim Ahemad Khatri, Mohamed Haji Isa (Mundra)

Bela

“Bela is 500 years old. Long ago, Bela was a big port and a trading post. Pakistan was closer than Rapar. That is why we were selling to Pakistan. We travelled to Sindh, Pakistan was on camel, bullock cart, horse, and donkeys. Rajputs, Koli, Rabnari, Lohana, and Vaniya community have always been in Bela. The Khatris came from outside but they have been here for many years now. The Saran River here is very sacred. It goes towards the rise of the sun and, and people come here for pilgrimage. Earlier it was always full of water. This river was the life line. Animals would come drink and people would come wash. All our Khatris would be here washing their cloths. But water has been gone for thirty years now.”

Artisan sources; Mansukh Pitambar Khatri (Bela)

Dhamadka

“The Dhamadka River was the only one in Kachchh that used to flow in the opposite direction. Usually the rivers originated in the Banni grasslands and flowed southwards. This one would empty itself into the Banni. The rangchulis were around the old river. There were thick date palm trees all around. The leaves of the date palm trees would fall off when dry. We used these as fuel. We didn’t need to go anywhere far for fuel. Everything used to happen at the river bank. Life in Dhamadka was peaceful and restful. We could open and close our shops when we pleased. Now people don’t have any spare time. They are constantly going here and there to complete work and orders.”

Artisan sources: Jabbar Khatri, Jhajibapa (both Dhamadka), Abdul Rauf Khatri (Ajrakhpur)

Rapar

“Traditionally we were making Batik by using clay and wax. We beat the clay and added the wax to it. We used lime to make a white color. People at Rapar were making Sadla for the Oswal and Kanbi Patel communities. The printing was done on raw cotton fabric known as “Pankoru”. Two prints were the most popular in those times. The “Kammarful,” which was worn by young ladies, and the “Tarkhendi,” which was worn by old women.”

Artisan sources: Abdul Rehman Rasool Soneji, Rapart and Ibrahim Isha (Ajrakhpur)

Chobari

“The Khatris migrated to villages like Chobari, Dhamadka, and Khavda where the rivers were flowing and the water was available in plenty. There was a big river in Chobari which was suitable for dyeing purposes. At that time there were few means of transportation, and we weren’t making cloth for distant communities. We were making cloth for nearby communities like Kanbi Patels, Rabaris, and Oshwal Jains. Our specialty was in the color maroon, which was very popular in the market.”

Artisan sources: Ibrahim Isha (Ajrakhpur)

Our cloth is their identity

Artisan sources: Razzaquebhai Khatri, Jabbar Khatri (Dhamadka), Dr. Ismail Khatri (Ajrakhpur), Abdul Rehman Rasool Soneji (Rapar)

“There was a carpenter, a weaver, and a potter in every village. The need for cloth in the village was met with the weaver of the village itself. The Khatri people would do the work of the bandhani, the printing, and the coloring according to the needs of each community. Traditional designs back then were very rigid. We did not have too much option to create something new. The communities each wore a particular design, and their identity was bound by that.”

Khatri Mohamedbhai Siddiquebhai printing the Morendi design, Dhamadka

The Khatris never wore block printed fabric. They produced cloth for maldharis (cattle herders), both Hindus and Muslims as well as farming communities across Kachchh. They used the barter system and exchanged cloth for produce from farmers, while cattle herders gave them milk or ghee. Each Khatri community specialized its work, producing textiles according to the needs and tastes of its clients. By having a specific client base for each printer, it was ensured that there was enough work for everybody.

“If there were 50 houses in a village of our clients, ten would be fixed for me, ten for my brother, five for my cousin, and so on. If there was a marriage in one of the families who was fixed with me, I would have the responsibility of making the clothes for all the family members. Just like pants and shirts are daily wear today, block printed lungis (dhoti), padas (skirts), and odhanis (veil cloth) were running items then. And people would buy more if there was a marriage in their family.”

The Khatris did not maintain any extra stock because they knew their clients so well that they could make cloth based on the needs of their clientele from the previous year. While there was a diversity of designs, they were not interchangeable among communities. Sales were so specific that it is still possible to find old textiles marked with the customer’s name or a code number given to a specific customer. The sale of cloth was either conducted in the workshop, or the artisan would hawk his wares from village to village, a practice now known locally as pheriya. Pheriya was restricted to particular times of the year, chiefly before the main religious festivals like Eid or Janmashtami. Sales were slow in the summer, as that was the time the maldharis would be away with their cattle looking for pastures.

An elderly woman in Mundra wearing a veil cloth; the plain body with only a border design are specific to older women

Maldhari man wearing Ajrakh lungi and turban in Banni

A Jat Maldhari groom with a traditional Ajrakh turban and shoulder cloth

Jimmi, the screen printed design imitating bandhani. It is worn by women between 50-60 years old from the Leva Patel community

We have walked all over the Banni

Artisan sources: Abdul Rahim Haji Sattar, Razzaquebhai Khatri (Dhamadka), Khatri Musa TarMohammed, Khatri Abdul Rehman Buddha, Dr. Ismail Khatri (Ajrakhpur

Jat Maldharis migrate all over Kachchh in search of water and fodder

“We used to work with the different Maldhari communities: Nodai, Haleputra, Sama, Sumra, and the Jat. the Maldhari community had a distinct style, a distinct color palette and design. They never changed styles and we never changed the Ajrakh design. You see, it was a source of identity for them. My grandfather would go to Banni with a camel cart to sell cloth to the Maldharis. He would be gone for days, he would stay at the homes of the Maldharis. Those were days of trust. So much respect for each other and friendship came first. Business was next. People had time back then.”

In Kachchh, Ajrakh was mainly produced in Khavda and Dhamadka. In earlier times the Khatris would spend some time of the year printing in their workshop, the remaining time they would be on the move to sell. Every Maldhari family working for them, and it was mutually understood that one would always do business with the same printers, hence there was no competition. There were two fixed times for sales - one after the rains and the other during winter.

“The Maldharis would come here to Dhamadka. Since they would be on the move with their cattle to Kathiawar, they would stop here en route. They would stay the night with us and leave the next day.”

Maldharis still wear Ajrakh cloth today. However, due to change in practices, the traditional hand block printed, natural dyed Ajrakh is no longer affordable for them. They purchase either the screen-printed substitutes or the Ajrakh block prints from Sindh.

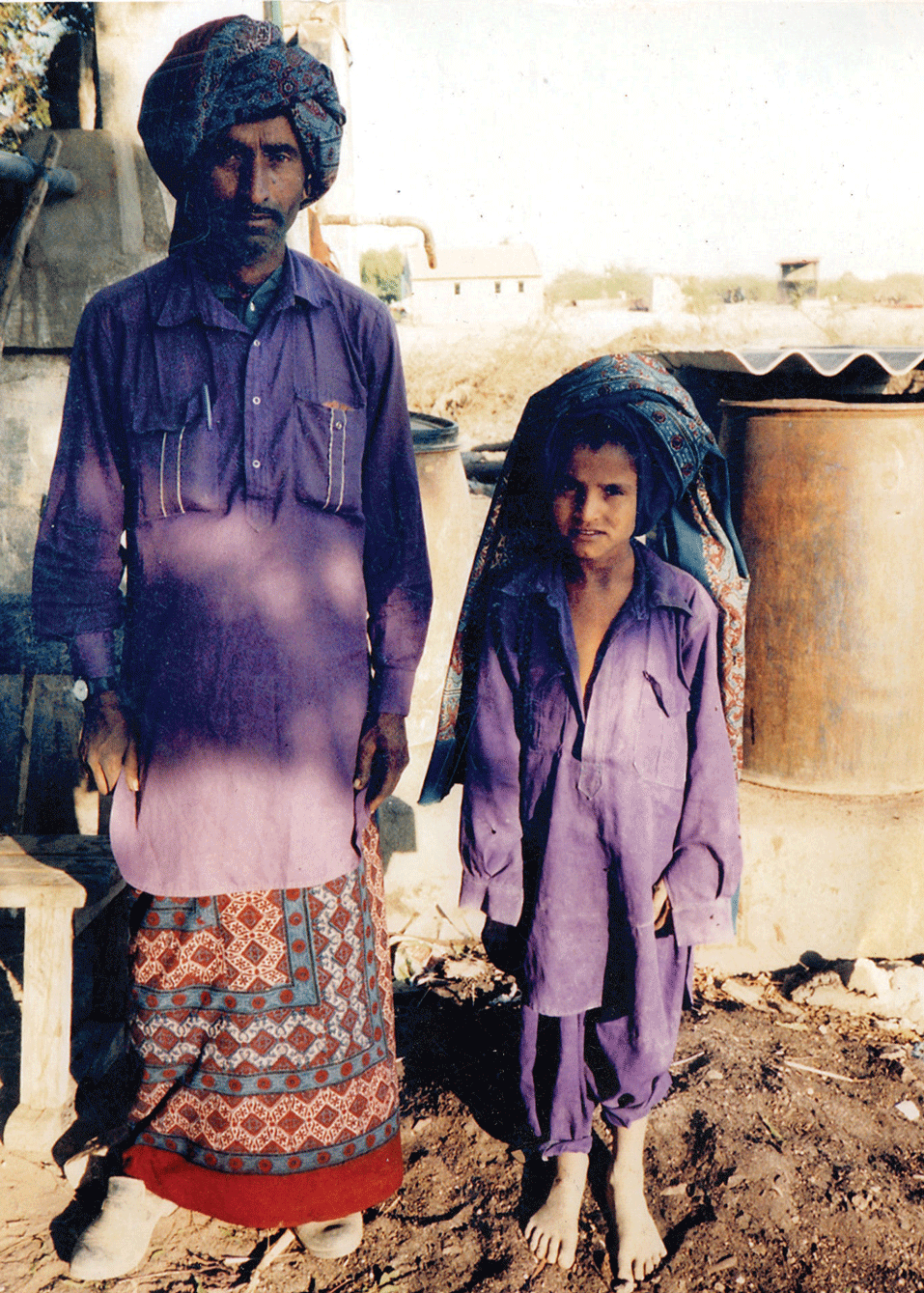

A Jat Maldhari couple; the Jat man is wearing a traditional Ajrakh dhoti

“Traditional double-sided Ajrakh was made using camel dungs. This was an 8 hour dyeing process. It is not practical in Kachchh anymore because of the time and labor required. It is not practiced in Kachchh anymore because of the time and labor required. It is practiced in Sindh however, and the smell it produces is associated with authentic Ajrakh. Khatris make traditional Ajrakh sometimes, but only on special order.”

To remove impurities and prepare for printing, cloth is soaked in a solution of castor oil, camel dung, and soda ash. This mixture is known as saaji. Cloth is left overnight to soak. The following day, it is laid out to dry in the sun. This process is repeated several times until the cloth foams when rubbed.

The country divided and we lost our trade routes

Artisan sources; Mansukh Pitamber Khatri (Bela), Abdul Rehman Rasool Soneji (Rapar)

Bela was the gate to the outside world for villages of the Wagad region of East Kachchh. There were more than 20 villages where Khatri families had settled and printing work was done mainly for the local farming community.

“We were working for Kanbi Patel (farmers), Jains, Lohana, Prajapati, Rajput, and Rabari communities. We were making chaniya (skirt) and odhani (veil) worn by the women. The designs were fixed and motifs evolved according to the age of the women wearing the skirt. In Bela, there were at least 50-60 Hindu Khatri families. There was a river in Bela that was ideal for washing. We used to collected indigo from Sindh. Other things like ghee, red rice (called Sindhi rice), and other vegetables like Kothimba were also coming from Sindh.”

Millet design, mud resist printed fabric from Bela. It was used by the women of the Patel community as skirts

Fabric from Bela showing the lavinginya design used by women of the Patel community

The Khatris obtained their raw material from Sindh through the port of Bela. In 1819 an earthquake severely altered the geography of the region and the port of Bela was shut down. Due to Bela’s proximity to Sindh, trade between these two regions continued by foot even after the port had closed.

In 1947, India and Pakistan were divided. It was no longer possible to cross the border and the trade between East Kachchh and Sindh collapsed completely. Soon, industrialization in India began which affected trade with the local communities who started wearing cloth produced by mills.

The Khatri artisans from other parts of Kachchh were badly affected by partition. Traditionally the Maldharis migrated between Sindh and Kachchh in search of greener pastures. Due to the new border, the Maldharis had to economize during times of drought. This was devastating, and also hurt the Khatris who relied on them for their business. The nomadic communities drastically reduced their consumption of textiles or stopped buying them altogether.

Traditional batik sadla worn by a woman from the Kanbi Patel community

Abdul Rehman Rasool Soneji, showing a piece of indigo from Sindh