Everything was broken

Dhamadka village in the aftermath of the earthquake in January, 2001

Disaster struck the region of Kachchh and the Khatris for the second time in 50 years. In 2001, a fatal earthquake took the lives and homes of thousands of people. Dhamadka, the heart of the block printing community, was completely destroyed. A tenth of the population died instantly.

There was a massive responsive nationally and internationally to the earthquake, and Kachchh became the focus of media interest. In Dhamadka, the Khatris started rebuilding their lives. But material loss was not the only problem.

“The iron content in the water increased drastically after the earthquake so we had to reduce our work with natural dyes. Iron in water gives you a black color while washing it with Harde [powder to prepare the cloth for better color absorption]. It makes the prints black and you cannot keep an off-white background. So many people bought farmland and dug bore wells in search of better water. But most of us shifted to working with chemicals and eventually stopped natural dyeing. Now we do it if there’s a need or an order - we have to take the pieces to wash somewhere else where the water has less iron.”

Even before the earthquake, the water level in Dhamadka was constantly decreasing due to an increase in bore wells. Water is the lifeline of printing and dyeing, so when the iron content in the water increased dramatically, the community had to make a decision: should block printing continue at Dhamadka, or not?

A new home

Artisan sources: Dr. Ismail Khatri, Khatri Musa Tarmohammed, Khatri Abdul Rehman Budda (Ajrakhpur), Khatri Dawood Latif (Dhamadka)

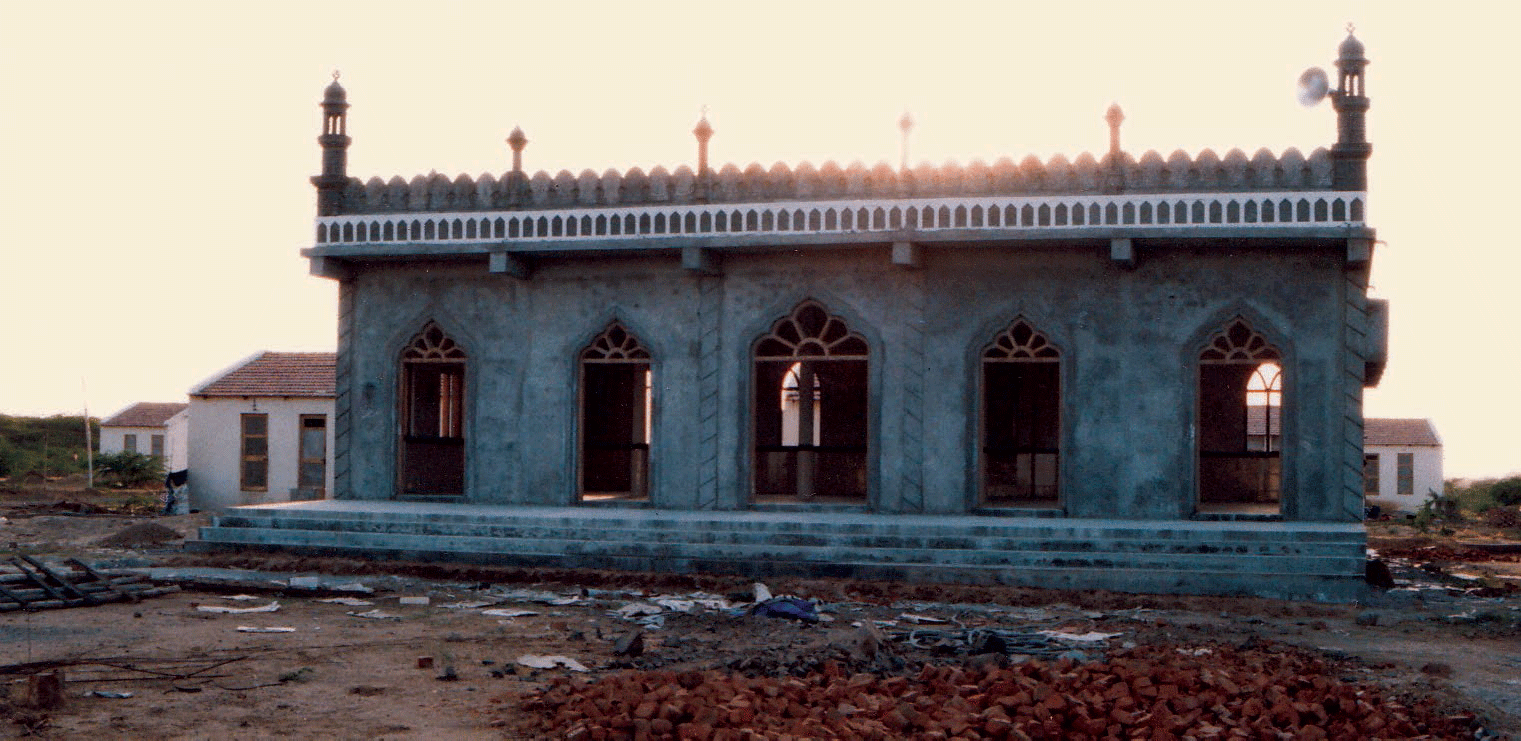

View of Ajrakhpur

“We decided to look for a new place. We thought about what this village should be. It should have good quality water source for our dyeing. It should be accessible for education, medical facilities, and business. In a sense, it should be a model village for block printers. So people from our village came together and bought land 40 kms away from Dhamadka. One member was identified from ten main families who would together take key decisions. We called the new village Ajrakhpur.”

“I had built a special shelf in my workshed where I stored all of my blocks. Then the earthquake came. the ground shook and everything was shattered. Those blocks were really dear to me. Some survived, but I did not carry them to Ajrakhpur. I started all over again completely when I moved to Ajrakhpur.”

For the first time in Kachchh, a village exclusively for printing craftsmen was built. This new village, Ajrakhpur, was set up not too far away from Bhuj. NGOs from the region helped to build homes and worksheds. A common washing area was built in the village where printing units took turns to do their washing. 12 years have passed since Ajrakhpur was founded. Today, it is a bustling craft village. It’s proximity to Bhuj has offered more opportunities to connect with traders, customers, and tourists. Currently, 80 Khatri families live in Ajrakhpur and the land offers capacity for more families to shift, which they plan to do in due time.

The Dalits of Dhamadka, who traditionally carried out printing for the Khatris, established their own “New Dhamadka” called Hastakala Nagari at another site. Most of the workshops there are not functional currently.

New expressions and explorations

Artisan sources: Khatri Khalid Amin, Khatri Razak Abdual Rehman (Ajrakhpur)

Today many Khatris work with international fashion designers and retailers. This opens more opportunities but demands high quality in work and innovative ways of design. The design school of Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya has empowered artisans to explore new artistic expressions.

“I get the inspiration for my designs from everywhere; the nature, the trees, the Kala Dungar, the stones, even this workshop and my tools in it. If you ask me to make a design based on the masons constructing outside this workshop, I can! My desire is to make something unique, something different from the rest and be known for it.”

A bedspread's central pattern showing traditional Ajrakh motifs combined in a new way

Despite new influences, Ajrakh is an enduring and iconic style and process that persists. It is interpreted in modern ways and printers play with new combinations of motifs, but Ajrakh can still be recognized for its intricate star shaped patterns interspersed into geometric borders and its deep indigo hues.

Many block printers are experimenting with technology in techniques and processes. To prepare a block printed cloth is a very labor intensive process. As finding workers has become difficult artisans started to adapt new technique to increase efficiency and reduce cost. Many attempts have been made to reshape traditional processes.

“We are using a compressor for our dyeing process now. Earlier it took one and a half hours to boil one load of fabric but now it takes 45 minutes to do the same thing. Also we need less wood for boiling because of the compressor. All wood pieces are burning very well inside the oven, so no extra waste is remaining. First time we have started this technique in Ajrakhpur, first with diesel engine, after that with electricity; so we are upgrading our workshop wherever it is possible.”

A drill is now used for blockmaking at Ajrakhpur

Block printers from Ajrakhpur exploring the use of a machine to treat the fabric with Harde, a practice usually done manually

Natural vs. Chemical

Artisan source: Dr. Ismail Khatri (Ajrakhpur)

A chemical dyes workshop in Mandvi

It often seems that there are two worlds of printing: the earthy colors of natural dyes rooted in tradition, and the contrasting bright and cheerful character of chemical colors. However, some printers serve both according to the demands of the market.

“People like vegetable more than chemical work but it is not possible to do vegetable work in Dhamadka. We are doing our work of vegetable dyes at other places like Ajrakhpur and providing the fabric to old customers.”

Today in the mid 2010s, there is a large demand for chemical dyed fabric. So the majority of the block printers are working with chemical dyes. Unfortunately, some of these dyes can cause serious skin allergies and respiratory problems. Meanwhile, working with natural dyes as a profitable livelihood requires more specialized skills and knowledge.

There is an ever increasing demand for natural dyes, even though it is not possible to produce all colors naturally. Indigo is available in synthetic as well as natural forms. Alizarine (red) is also available as a synthetic dye. Both are eco friendly.

Interestingly, chemical printers in Kachchh have adapted the resist technique to chemical printing. The resist materials remain natural, a mixture of gum and lime, while the pigments and dyes are chemical. This technique is used by hand block printers and some screen printers as well.

These days we use Whatsapp!

“Clients call me themselves, or these days they have started Whatsapping me. In a second, the design gets fixed and the order gets finalized. We should take care of our customers when they visit us and make them understand about the value of our work. We need to give them respect and listen to their opinions. If they are happy then one happy customer will go back and tell ten others, those ten will then tell hundreds, then thousands. This is advertising. This is how our name spreads.”

Today, Khatris are just as much businessmen as they are block printers. Some Khatris haven’t actually printed in years because they manage large workshops of people who do their printing for them. The modern market demands year-round production, and so the Khatri business model has changed substantially. Now, the Khatris print surplus stock in order to prepare for new clients and seasonal change. The monsoon is a slack period for production since the humiditiy affects the printing and dyeing quality, and there is no place for drying.

While there is vibrant competition in Dhamadka and Ajrakhpur, East Kachchh has witnessed a slow decline in printers and dyers.

“I am the only block printer left in Bela. I feel I can benefit from it, because today there is no competition for me anymore. Earlier there used to be three or four people working, so everyone tried to cut costs and earning would never go up. It did not make sense to invest in new blocks and experiments since I could never be sure of recovery. Now, I can invest in my designs. The Rapar trader makes bags and jackets from my cloth, or he gets them embroidered, and sells them to other markets.”

We are running out of water

Artisan source: Mansukh Pitambar Khatri (Bela)

“We came to Ajrakhpur because of the water problems in Dhamadka. But the problem of water still persists because the level of water has been going down by 10-15 feet every year even here. We have to seriously think and plan for the future.”

Water is the lifeline of printing and dyeing. As long as the scale of production remained local, there was plenty of water for everything. In Dhamadka, the river Saran was always flowing, but it died a slow death by 1989. This was largely due to the increase in bore pumps which diverted the water towards the Kandla Free Trade Zone. There was no planning to collect rain water and recharge the depleting water tables. After the earthquake of 2001, there were upheavals in the geo-hydrology of the region. The water tables suddenly showed a high content of iron which made it untenable for printers to do their work with natural dyes. Drinking water now has to be got from a village further upstream from Dhamadka.

While Ajrakhpur was selected due to its good water source, the water tables are lowering and the need of a sound water management plan is being discussed by the block printers along with various organizations and experts. As of yet, a comprehensive plan has yet to emerge.

“There is a very old river in Bela called the Saran. We’ve been washing here in this river for years. For the last 20 years, this river has been dry, so we have to go back to the bore well now to wash. Earlier, this river would always be filled with water and it would also be filled with the Khatris washing their cloth.”

Elsewhere, in Khavda and Bela, the water continues to pose its own problems. The Khavda printers now work only with chemical dyes due to the quality of water in their village, incurring skin allergies as a result. In Bela, a lone printer now trudges to a bore well to do his washing because the plentiful river which once supported a village of 50 block printers has dried up.

Washing at a farm in Dhamadka

Working with our mind, our hands, and our heart

Artisan sources: Khatri Musa Tarmohammed (Ajrakhpur), Shakil Ahmed Khatri (Mundra), Qasim Khatri (Mundra)

“The future of Batik is very uncertain. So many workshops have closed over the past few years. I do not really know what will happen in my son’s generation. But while I am still here, I cannot bear to close down my father’s workshop. It has been build though the blood and sweat of my forefathers. My emotions are associated with it. I will keep it going.”

“Children typically help out in production while they study so that they can build up their learning bit by bit. If they feel, once their schooling is over, that they would like to continue, then they join full time. There is no pressure to remain in the profession. I would rather than the children join it out of love of the work than feel forced. While one of my sons works with batik, the other was keen to learn computers and he now has an office job. He could help us in marketing and reaching foreign markets.”

Like traditional crafts everywhere, the future often feels uncertain. But in Kachchh there are both fears and hopes. There is an emerging younger generation that sees the potential and growth of their traditional businesses and dare to imagine new futures. They see learning design, dyeing chemistry, computers, and management as linked to progress. Some have experimented by setting up model workshops with new tools and equipment in response to the demands of the new markets they engage with. Also, breaking social ranks, some of the Dalit workers of the Khatris have set up their own successful workshops. All this ferment will ensure that the essence of working with heart, mind, and hand will continue for a long time.

Children learn the art of dyeing when they are very young

The making of a block requires great precision and concentration

Block printer in Bela